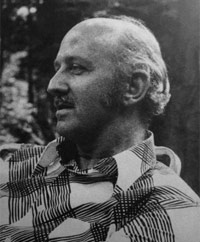

J. Louis Martyn 1925-2015

Tuesday, June 16, 2015

|

|

Photo by Fleming Rutledge

Rye Brook, NY, c. 1980

|

When a great and beloved teacher dies, it rallies his students from all around the world. Email is not always a blessing, but in this case it certainly has been a privilege to share in an outpouring of grief and gratitude. We are like brothers and sisters to one another, rejoicing in the privilege we had of studying with, and knowing personally, one of the most important New Testament scholars of the second half of the 20th century. His influence and reach was conveyed well into the 21st century, particularly at a 2012 conference on Romans where he was honored guest and participant in a gathering of scores of scholars from the US, Canada, Europe, and Australia. The importance of his work for the future has already been presaged by Apocalyptic and the Future of Theology: With and Beyond J. Louis Martyn, edited by Joshua B. Davis and Douglas Harink (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2012).

Lou Martyn was not only a supreme interpreter of the letters of the apostle Paul–and, earlier, of the Fourth Gospel; he was also an authentically nurturing father figure. It is not given to every doktorvater to exercise the role of vater as well as that of doktor. In this, Lou Martyn excelled. We will all cherish the way he adopted us, supported us, radiated pride in us. To the end of his life his intensely affirming way of greeting us and conversing with us at meetings, gatherings, and other occasions of greater family intimacy was precious to us. He was not without his acerbic side; I’m sure that all of us felt his displeasure from time to time if we disagreed with him. Yet he never ceased to care deeply about each of us and our families in addition to encouraging us in our vocations.

The originality of his work will surely never cease to gain admirers. His unique voice was unmistakable and could never be mistaken for anyone else’s. It was much more literary than that of most textual scholars. Vivid imagery came naturally to him, and he never seemed to be at a loss for a novel way of expressing his ideas. He said that the Corinthian congregation “grabbed the ball Paul passed to them and ran out of the stadium with it.” He spoke sadly of a troublesome colleague, “He doesn’t believe that he’s justified.” He mused that not everyone would appreciate Barth, but you couldn’t be a theologian “unless you lost your virginity to Barth” or unless, somewhat less startlingly, “your citadel had been stormed by Barth.” He didn’t give many lectures, greatly preferring the round table, but I remember one occasion at Union in the tumultuous early 70s when a student challenged him, saying that “there are other gospels.” In front of a filled lecture hall, JLM looked directly at him and said, steadily, “Yes, and Paul wrote, ‘If anyone is preaching to you another gospel, let him be accursed’ [the essence of Galatians 1:8-9].” It was one of the most electrifying moments of my seminary years.

The years at Union in the 70s and 80s were extremely contentious and difficult. Samuel Terrien intemperately referred to the group overhauling the curriculum as “the theological Mafia.” Lou had his own way of referring to “Seminary A” and “Seminary B.” (Perhaps he would not like my quoting him on this, but I’m doing it anyway.) Seminary A was made up of the faculty who taught the classical disciplines and the students who prized their courses. This faculty included Raymond E. Brown, Terrien, Cyril C. Richardson, Paul L. Lehmann, and Richard A. Norris, Jr. among the professors, Christopher Morse among the (then) assistant professors, and such obstreperous adjuncts as Marcia Weinstein who was indignant that anyone would suggest that there was a “female sensibility” in teaching and learning. Seminary B had some famous names also, but was more ruled by the Zeitgeist, supporting various political agendas and setting constituencies against one another. Although I considered myself a feminist of sorts, I was nowhere near feminist enough for Seminary B. I can truthfully say that I would have been utterly lost in Seminary B, and was headed in that direction, until in my second semester one of the deans wisely guided me to Lou Martyn’s courses. It was one of those interventions in one’s life that made all the difference.

Beverly R. Gaventa, who was the same M.Div. class that I was, went on to become an honored professor of New Testament specializing in Paul. She and Robert T. Fortna compiled and edited a Festschrift for Martyn (Abingdon, 1990) called The Conversation Continues. Every Martyn student will recognize the aptness of this title. He spoke often of the hermeneutical round table, where interpretations were hammered out in the lively exchanges among the participants. This sometimes proved frustrating for me, because I wanted to know what Professor Martyn thought, not what some other student thought! but in the final analysis I learned to have deep respect for this way of reading Scripture not only in the academy but, even more, by the church.

Beverly Gaventa wrote this about our friend and mentor:

Names, dates, publication titles — these all come easily to expression. What is far more challenging to convey to those who did not know him is the character of the man. I have heard the word ‘Mensch’ invoked often for him, and that may be the best we have. For all his brilliance, Lou was not concerned with being brilliant. He squirmed at the expression ‘Martyn School.’ He cared about the subject matter. What counted was Paul, or as Lou would say, ‘taking a seat in the early Christian congregation’ without succumbing to the temptation ‘to domesticate the text, to cage the wild tiger.’ (Theological Issues in the Letters of Paul, 211-12.) Lou also would say, ‘Life is more than work.’ He was utterly devoted to his family… [and] his many students and friends could be forgiven for thinking ourselves part of that extended family as well… Little in my life can match the pleasure of picking up the telephone and hearing that unique voice, ‘Is this the Professor Gaventa? Do you have a minute?’

All of Lou’s students are, I’m sure, proud that our academic genealogy includes Ernst Käsemann as a grandfather, but the name of J. Louis Martyn will be proudly cited for generations yet to come as the one who perhaps more than anyone else in his time brought the radical apocalyptic perspective into the wider academy where it is now percolating down into the pews. He reoriented my homiletical thinking entirely, away from myself, my perceptions, and my experiences to the God and Father of Jesus Christ, and to the proactive grace of God, which does not make a move and then stand back and wait to see what we will do next (he called that “a two-step dance”), but remains powerful in the present and future, so that as the Book of Common Prayer says, “all our works [are] begun, continued, and ended in thee.”

Lou’s partnership with his wife Dorothy was very important not only in the usual manner of blessed long-married couples, but also, notably, in their intellectual compatibility. As an esteemed psychoanalyst with a doctorate in theology, Dorothy was so much in tandem with her husband’s biblical anthropology that it was hard to tell them apart. Her story about a child in the treatment room, playing with toy soldiers and saying, “The enemy lines are hard to find,” found its way into one of my sermons. I have often used her story about being rejected for jury duty. She said, “I’m never chosen. I just tell them [truthfully] that I don’t believe in guilt and innocence.” Her two books The Man in the Yellow Hat and Beyond Deserving are deeply theological in their understructure. Perhaps my most cherished personal memory of them is this: when I was just out of three weeks in the hospital, still in a thigh-high cast, and our daughter was in another hospital with a brain tumor, the Martyns drove all the way from New Haven to our home, bringing dinner for us and our children’s grandparents. That, indeed, was grace in action.

Not a day goes by that I don’t hear Lou reminding me of the prevenient grace of God, that God is the subject of the sentences, and that there are no imperatives without enveloping indicatives. Nor do I think of him without the deep affection and comradeship he shared with Paul Lehmann when they were both colleagues at Union. The official statement from Union speaks of Louis Martyn and Raymond Brown together, and that isn’t wrong, certainly; they were friends, admired one another, and were–obviously–the two towering figures in the New Testament department. The deepest personal and theological bond, however, was with Lehmann. Their cross-disciplinary friendship, though it came relatively late in their lives, was strengthening in fundamental ways for both of them, and now also, for younger scholars who did not even know them personally.

The conversation continues….